Born around 1832, possibly in Tennessee, Mary Fields celebrated her birthday on March 15. The details of her life before she came to Montana in 1885 are difficult to trace—complicated by her birth into slavery and the fact that, although she was literate, she left no written record. According to one biographer, Fields’s mother was a house slave and her father was a field slave. After the Civil War, Fields worked as a chambermaid on the Robert E. Lee, a Mississippi River steamboat. According to some accounts, she met Judge Edmund Dunne while working on the Robert E. Lee, and eventually became a servant in his household.

In the 1870s, Fields began working at the Ursuline Convent in Toledo, Ohio, where Dunne’s sister, Mother Mary Amadeus, was the superior. In 1884 Mother Amadeus traveled to Montana to join the Jesuits at St. Peter’s Mission. The next year she wrote to request that the convent send more people to staff the struggling mission and boarding school. Mary Fields traveled upriver with the nuns sent by the order.

Thus Mary Fields began her new life among the sisters in Montana. She worked at the mission for the next ten years, raising chickens, growing vegetables, and freighting supplies from nearby Cascade. She developed a reputation for having “the temperament of a grizzly bear,” but tales also spread about her toughness and devotion to the nuns and students.

Because of her tendency to smoke, swear, and bicker with other hired hands at the mission, Fields drew the ire of Bishop Brondell, of Great Falls, who banned her from the mission around 1894. Though the nuns defended Fields, they had no choice but to follow the bishop’s orders, and Fields, reportedly devastated, moved into Cascade.

After two failed attempts at running a restaurant, Fields secured a contract to deliver mail to St. Peter’s Mission. She earned the nickname “Stagecoach Mary” for her reliability and speed, and she drove the fifteen-mile route between the mission and Cascade from 1895 to 1903. She was around seventy years old when she finally “retired” in town and ran a laundry out of her home. She died in Great Falls in 1914.

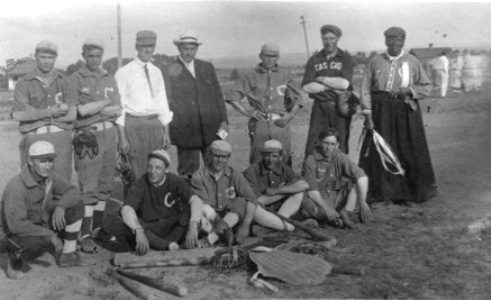

In many ways, Fields transcended the traditional gender boundaries for women of the era. She neither married nor depended on the support of the church. Handy with a gun, she smoked, drank, and swore and took a “man’s job” delivering mail. Because she was a large woman, she wore men’s shirts and jackets. She also socialized with men at the baseball field and in the saloon. In a 1959 issue of Ebony, Montana-born film star Gary Cooper reminisced that Fields could “could whip any two men in the territory” and “had a fondness for hard liquor that was matched only by her capacity to put it away.”

The Mary Fields of legend is a masculine figure; her traditionally feminine attributes are typically underplayed. Yet Fields generally wore skirts, loved to grow flowers, and babysat many of Cascade’s children. A subtle racism may explain this discrepancy. The people of Cascade accepted Fields while she was alive and celebrated her after death, but historian Dee Garceau-Hagen points to nicknames like “Black Mary,” “Colored Mary,” and “Nigger Mary” and argues that Cascade residents “affirmed a caste system based on race, even as they celebrated Fields’ notoriety.”

As the sole African American in Cascade, Fields did not have the benefit of a close-knit black community, such as developed in towns like Helena, Great Falls, Butte, and Fort Benton. And because she was also “outside the boundaries of respectable womanhood,” Fields was in some ways on her own. It is hard to imagine that Fields did not feel the sting of prejudice, or at least the “friendly contempt” described by African American musician W. C. Handy on a visit to Helena in 1897. Nevertheless, she certainly lived an inspirational life—and one forged on her own terms. A writer for Negro Digest in 1950 cast her as a role model: ““She was, in the best sense, a pioneer woman. She was rough and she was tough.” And as Gary Cooper opined, she was born a slave, but “lived to become one of the freest souls ever to draw a breath or a .38.” AH

Interested in learning more about African American Montana women? Read these posts on Alma Smith Jacobs and Rose Gordon.

Sources

Behan, Barbara Carol. “Forgotten Heritage: African Americans in the Montana Territory, 1864-1889.” The Journal of African American History 91, no. 1 (Winter 2006), 23-40.

Cooper, Gary, as told to Marc Crawford. “Stagecoach Mary: A Gun-Toting Black Woman Delivered the U.S. Mail in Montana.” Ebony (October 1959), repr. Ebony (October 1977).

Garceau-Hagen, Dee. “Finding Mary Fields: Race, Gender, and the Construction of Memory.” In Portraits of Women in the American West. London: Routledge, 2005, 185-242.

Graham, Art. Review of James A. Franks, “Mary Fields: The Story of Black Mary.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 53, no. 1 (Spring 2003), 74-75.

Harris, Mark. “The Legend of Black Mary.” Negro Digest, August 1950, 84-87. Copy in Fields, Mary, Vertical File, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Lang, William. “The Nearly Forgotten Blacks on Last Chance Gulch, 1900-1912.” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 70, no. 2 (April 1979), 50-57.

Life of the Rev. Mother Amadeus of the Heart of Jesus. New York: Paulist Press, 1923. Copy in Fields, Mary, Vertical File, Montana Historical Society Research Center.

Nash, Sunny. “Mother Amadeus and Stagecoach Mary.” True West, March 1996. Copy in Fields, Mary, Vertical File, Montana Historical Society Research Center.

“Old Timer Passes Away,” Cascade Courier, December 14, 1914. Copy in Fields, Mary, Vertical File, Montana Historical Society Research Center.

Shirley, Gayle C. “Mary Fields: The White Crow.” In More than Petticoats: Remarkable Montana Women. 1995; repr. Kearney, Neb.: Morris Book Publishing, 2011, 1-5.

Sister Genevieve. “Mary Fields.” In Mrs. Clarence J. (Conrad) Rowe, comp., “Mountains and Meadows: A Pioneer History of Cascade, Chestnut Valley, Hardy, St. Peter’s Mission, and Castner Falls, 1805 to 1925,” 157. Copy in Fields, Mary, Vertical File, Montana Historical Society Research Center.

Mary Fields is someone i want to know more about!

Are there any things in Montana that commemorate her? Is her grave marked?

mary lands is an a good story life.